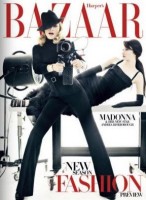

![Madonna: The Director’s Cut [Full Harper’s Bazaar Spread]](https://www.madonnarama.com/artworks/posts/en-6475.jpg)

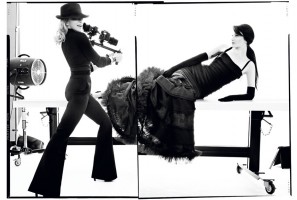

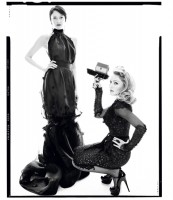

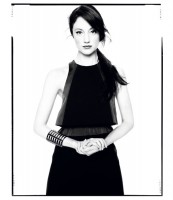

On the release of her film, W.E., the superstar talks women, power and sexuality. Read the interview below, plus see her fashion shoot with actress Andrea Riseborough.

Madonna lives behind high, spike-topped, black metal walls in three townhouses joined into one on New York’s Upper East Side. I had to manage my covetous feelings as I was ushered through the gate and then walked through pristine living rooms, dining rooms, and sitting areas, all decorated like the highest end of British hotels, in a mélange of blacks and grays. There were glossy black floors and doors, original Tamara de Lempicka paintings on the walls, and, I would swear, a wall covering made of teal duck feathers in at least one bathroom. But I was open to forgiving Madonna all of these signs of her success because the fact is, I think the woman is gutsy, and the risks she has taken in her career have made the world a bit freer and more interesting for women of my generation.

In person, Madonna is tiny and alarmingly fit, and she has the posture of a seasoned dancer. Her face is more delicate than in photos; one gets the sense that she is aware of her every gesture. She is wearing beige slacks with boots and a belted beige sweater over a white shirt; her hair is simply styled in blonde waves. She greets me warily and welcomes me into a quiet study.

Then the surprises begin. Throughout my formative years, when she was so iconic, I had always assumed that Madonna had been brave in her choices because of some innate egotism or some aberrant strength of will. In person, I discover that she has been brave in her life in spite of lacking certain kinds of protection, privilege, and confidence. What I hadn’t expected to feel was moved. At 53 years old, I find, Madonna is scrappy, really smart, and young in the way that people who have had a childhood trauma — she lost her mother when she was five years old — often seem to be. She is very guarded at times and then, as we speak, more open, even vulnerable.

“For some reason, I feel like I never left high school, because I still feel that if you don’t fit in, you’re going to get your ass kicked,” she says. “That hasn’t really changed for me. I’ve always been acutely aware of differences and the way you are supposed to act if you want to be popular.”

I have always been intrigued with Madonna as a provocatrix, and her latest venture is no exception to that record. Her new directorial project is W.E., a cinematic version of the story of Wallis Simpson, the American divorcée for whom British monarch King Edward VIII famously abdicated the throne in 1936. It premiered at the Venice Film Festival this fall to mixed reactions and will open stateside in December. “Making movies is really hard. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” she says.

The film, which Madonna also cowrote, juxtaposes Wally (Abbie Cornish), a modern-day trophy wife who has everything on paper but is trapped in an abusive relationship, with a mythical version of Wallis Simpson, played by Andrea Riseborough. The two women’s stories intertwine when Wallis enters the mind of the later Wally and serves as a kind of muse and mentor to her, attempting to spur the young woman from depressed passivity to agency in her own situation. “Get a life,” Wallis says sharply to Wally in one of my favorite scenes.

“I believe sometimes we aren’t always in charge of everything that we do creatively. We submit to things as we’re going on our own journey,” Madonna says. “Wally was learning about herself, and so was I — on my own journey and the journey of all women. I don’t work any other way.”

She was drawn to the subject precisely because of how polarizing a figure the Duchess of Windsor remains — an issue with which she identifies. “When I brought up the subject of Wallis Simpson to people when I was living in England, I was astounded by the outrage that was provoked by her name,” Madonna says. “The movie is all about the cult of celebrity,” she adds. “We like to put people on a pedestal, give them one character trait, and if they step outside of that shrinelike area that we blocked out for them, then we will punish them. Wallis Simpson became famous by default, by capturing the heart of the king, but it’s obviously a subject I’m constantly on the inside of, and the outside of.

“I think my behavior and my lifestyle threaten a lot of social norms, like the movie does,” she observes. “I think there are a lot of parallels and connections.” For her star, Andrea Riseborough, it was liberating to work with such a powerful woman on a female-centric film. “I was interested in the strong, interesting person apart from the public persona, and I was not disappointed,” she says of Madonna. “I found it hugely fulfilling.”

Madonna’s work is always strongest when she reaches into archetypes, and this film places the emergence of a woman from victim status (actually, of two women; Wallis Simpson also was abused in her first marriage) to mistress of her own destiny at the heart of the storytelling. That focus on a woman’s journey is very rare in major feature films. The role of men in the film is also radically unusual: They are presented allegorically — the villain, the sex object/nurturer — in a way that women characters are usually portrayed in relation to the male hero’s journey.

Some of the critical hostility Madonna faces with this film, I am sure, is a reflex — our culture’s resistance to women having power; directing a feature film is a powerful role, and women are central to this movie. I work with young women, I am the mother of a daughter, and I wanted to know, how did Madonna’s sense of self emerge so intact? “I don’t really know how,” she replies. “I think it’s just that as a creative person, in all the different things that I’ve done or ways that I’ve found to express myself, I’ve consistently come up against resistance in certain areas. I think that the world is not comfortable with female sexuality. It’s always coming from a male point of view, and a woman is being objectified by a man — and even women are comfortable with that. But when a woman does it, ironically, women are uncomfortable with it. I think a lot of that has to do with conditioning.”

I press further, wondering how exactly she escaped that conditioning. “The fact that I didn’t have a mother helped me in some respect, and that I didn’t have a female role model. I was always very aware of sexual politics, growing up in a Catholic-Italian family in the Midwest, seeing that my brothers could do what they wanted but the girls were always told that they needed to dress a certain way, act a certain way. We were told to wear our skirts to our knees, turtlenecks, cover ourselves and not wear makeup, and not do anything that would draw attention. One of my father’s famous quotes — and I love him dearly, but he’s very, very old-fashioned—was ‘If there were more virgins, the world would be a better place.'”

“Wow, Papa,” I say, laughing. “I’m sure he wouldn’t say that now,” she says. “He’s probably cringing. Obviously, that was when I was young. And then, going to high school, I saw how popular girls had to behave to get the boys. I knew I couldn’t fit into that. So I decided to do the opposite. I refused to wear makeup, to have a hairstyle. I refused to shave. I had hairy armpits.”

The young Madonna was “tortured.” “The boys in my school would make fun of me,” she continues. “‘Hairy monster.’ You know, things like that.” It wasn’t until her teenage years, when she began hanging out at gay clubs, that Madonna started to find herself. “Straight men did not find me attractive,” she says. “I think they were scared of me because I was different. I’ve always asked, ‘Why? Why do I have to do that? Why do I have to look this way? Why do I have to dress this way? Why do I have to behave this way?'”

The nature of some of Madonna’s questions has changed, especially as she now has four children: Lourdes, 15; Rocco, 11; and David, 6, and Mercy, 5, who were both adopted from Malawi. I ask about her mothering philosophy. “Well, I say to Lourdes, schoolwork always comes first, so anything that gets in the way of that falls by the wayside. We put our energy in education.” So how does Lourdes manage her schoolwork and a clothing line (Material Girl, which launched last year)? “She loves fashion and style. She helps design the collection. I just stand in the background and watch. I proofread her blogs and edit them and give her a hard time when I think she’s being a lazy writer.”

She adds, “I also encourage all of my children to ask questions and investigate. I never want my children to come to me and say they want to do something because everyone else is doing it. That doesn’t interest me at all. You need to tell me your personal reasons about why it will benefit you, what you’re going to get out of it, what it means to you. Otherwise, you’re just a robot. You’re not thinking for yourself. Where would you go with your life with this kind of attitude?”

Madonna is frank about the impact her celebrity has on her kids: “The other day, I was out on the street with Lourdes. She wasn’t feeling well and had a fever,” she says. “She was wearing her tracksuit bottoms and her T-shirt, and she turned around and was like, ‘Ugh, there’s a paparazzi, and I look like shit!’ I felt for her because, you know, I thought, this is an extra layer. It’s already a challenge to have a teenager, then to have a teenager in New York City, and on top of that, she’s the daughter of someone famous. It’s a lot. I’m aware of it, and I constantly find myself apologizing for it. But it also provokes many discussions with us about what’s real and what isn’t real.”

In addition to handling a new country and set of schools as a single mother (she moved back to New York two years ago), Madonna is in a relationship; she is currently seeing French breakdancer Brahim Zaibat. I speculate, as a single parent myself, about whether the new model her setup represents (a successful single woman who has her work and her kids and who has taken a lover — or lovers — simply because he makes her happy) is threatening to patriarchal boundaries around the idea of family life.

“Well, it can also be more than just sexual, um, appendages,” Madonna answers. “I don’t necessarily like to use the word lover because it sounds like they just come over and have sex with you. I aspire to more than that, and I need more than that.”

Like what, exactly? “Someone to share my inner life with. That’s extremely important. It’s also important that my children admire and respect this partner that I would choose for myself. Especially for my sons, who have their father [ex-husband Guy Ritchie], but they need a male role model as well. So I need to keep this in mind: What is this person modeling to my sons, what kind of man is he, what values does he have, what energy is he giving off? Because they are impressionable. It’s so important.”

What qualities does she most want her sons to see in a partner of hers? She replies, “Respect for women and understanding that everything must be earned. Those are two big ones.” Wallis Simpson, of course, had an intriguing reputation as a sexual sorceress. “I seriously doubt it’s true,” Madonna says. “But she was a powerful woman, so it makes sense that people would make things up about her. When women are perceived as powerful and doing something they aren’t supposed to be doing, they are often portrayed as sexual predators.

“They said that because they couldn’t understand how she won a king,” she explains. “She wasn’t conventionally pretty, she had the body of a teenage boy, she was divorced twice, and by the time she married the king she couldn’t have children. What did she have to offer? She’s not pretty, fertile, or a virgin, so she’s useless. I was actually told once by a Japanese woman that there’s a phrase for women who are past the marrying age: ‘stale cake.'”

Madonna points out that her own age is always a focus. “I find whenever someone writes anything about me, my age is right after my name,” she says. “It’s almost like they’re saying, ‘Here she is, but remember she’s this age, so she’s not that relevant anymore.’ Or ‘Let’s punish her by reminding her and everyone else.’ When you put someone’s age down, you’re limiting them.”

She says, “To have fun, that’s the main issue. To continue to be a provocateur, to do what we perceive as the realm of young people, to provoke, to be rebellious, to start a revolution.”

—

Article by Naomi Wolf for Harper’s Bazaar

Pictures by Tom Munro

Alternative Cover by Matthew Rettenmund of Boy Culture

Madame X is available in Box Set, CD, Vinyl and Cassette!

Get your copy HERE!